Even though I love to read and always have, I sometimes forget what doors to other worlds it can open, until the sheer fact of it hits me in the face.

Just today, I read from a fascinating story in the Washington Post about a 76-year-old Brit who completed his Ph.D. thesis this month— 50 years or so after starting it. He’d thought about the topic throughout the intervening decades, honing his ideas with lived experience.

A brief example:

“When Nick Axten restarted his doctorate in philosophy after a four-decade hiatus, he loved taking the hour-long bus ride to the University of Bristol campus each day. While he sat with his thoughts, others sat on their phones. He said the ride was a uniquely productive time to flirt with solutions to his work in his head.

Academia used to think bigger, said Axten, 76, and universities were more concerned with their students learning something new, rather than simply finding their next job.”

According to the Post, his thesis holds that “people’s decisions are based on criteria that include the number of choices available, the likelihood any one choice will pay off and how far into the future that payoff might be. Axten hopes the research can be used to better predict how people will act in a range of typical situations.”

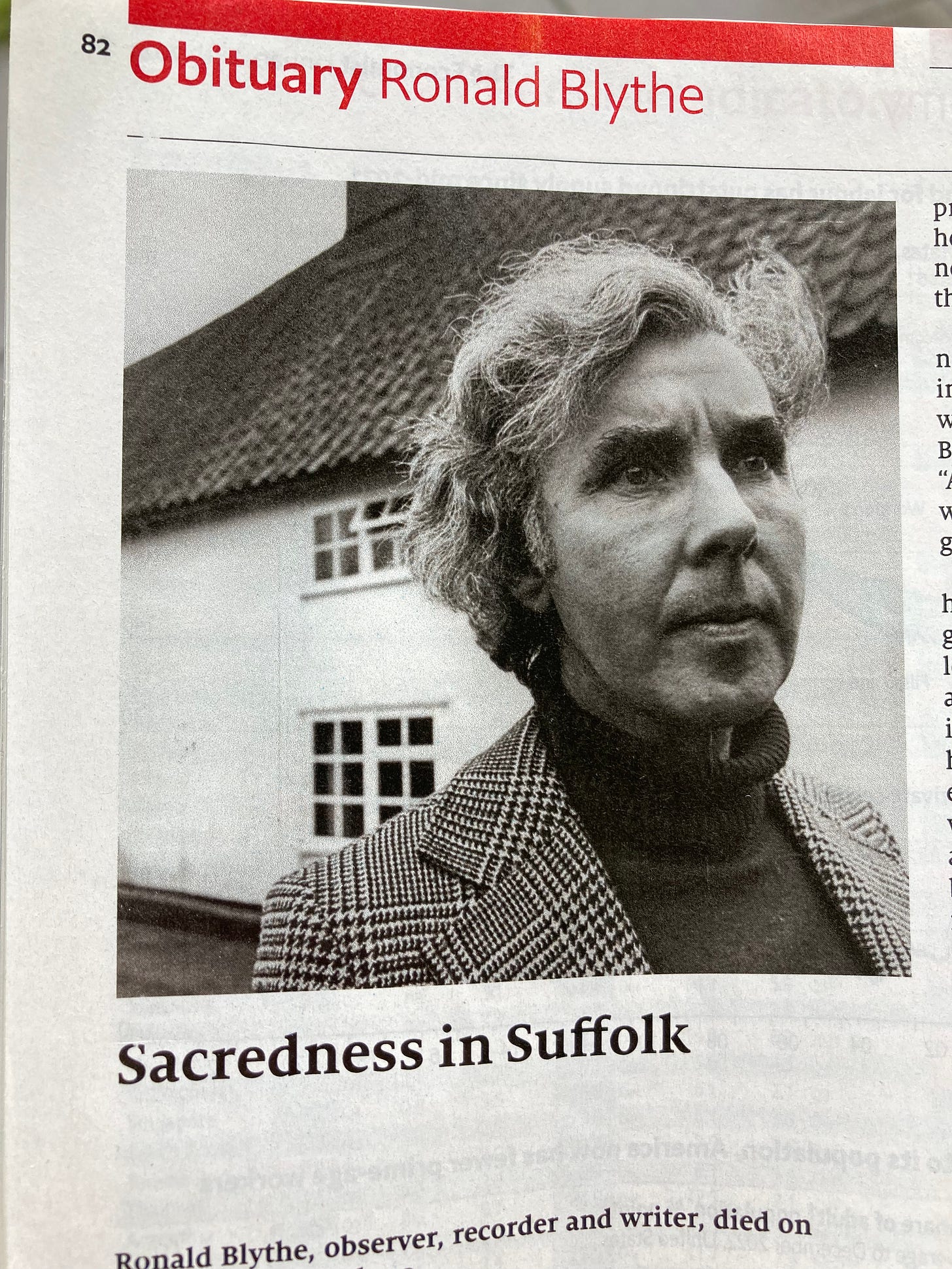

Then, flipping over to The Economist, I discovered a wonderful obituary of an English writer I may have heard of in passing but never knew much about, Ronald Blythe. Blythe, a largely solitary soul in Suffolk, gained fame for a time for his book called “Akenfield,” based on interviews with villagers in the vicinity, blacksmiths, thatchers, gravediggers, and other “rural labourers.”

These rugged rural folk, despite being white and European and now almost certainly dead, were in no sense privileged, and could hardly have been further from the center of the life of their time. But it made me glad to read that their lives and words were salvaged, by Blythe, from total obscurity and oblivion.

Blythe lived in a world most of us now can only imagine, a rural, mostly lonely life in an agricultural area northeast of London where many locals answered queries, at least at first, with “bony quiet,” and young boys like Blythe could explore country lanes or watch clouds flit across the sky without much in the way of adult supervision or even attention. Solitude, the obit’s writer surmises “though broken by dear visitors and his imperious cats, was good for writers.”

He died January 14th; he was 100 years old.

One last example. I’ve finished about one-third of an amazing book by Daniel Mendelsohn, “The Lost: a search for six of six million,” an exploration of his search, decades later, for the facts, context and meaning surrounding the deaths of six relatives lost in the Holocaust. The book takes one deep into the horrors of that cataclysm, but explores also much about family, history, myth, strife between peoples, strife between brothers, Jewish tradition, commentaries on commentaries on the Torah, and much else, woven together in overlapping, intersecting sections. Tragic, but strangely full of laughter and love and budding self awareness.

Mendelsohn has also written a fascinating book about The Odyssey—“The Odyssey: A Father, a Son and an Epic," that similarly weaves deep scholarship with family history, psychological exploration and travel in a uniquely personal way.

His books make me wish I could have taken Professor Mendelsohn’s seminars — and make me recall, with pleasure tinged with regret, some of the wonderful literature and history professors I studied with and didn’t always fully appreciate at the time, an eternity ago, it now seems.

Wonderful!